Abstract | PDF | Volume 1 (April 2019) | Request Permissions

Same Image, Different Lens: Revisiting the Critical Reception of Two Different Generations of Cinematic Superheroism

Kaitlyn Adier Cummings

Biography | Notes

Keywords: female superhero, feminism, postfeminism, film criticism, genre studies

Introduction

Hollywood has not been kind to the female superhero. History shows the superheroine has rarely been given a cinematic stage of her own, instead often relegated to an auxiliary role as sidekick (Storm, X-Men; Black Widow, Iron Man; Wonder Woman, Justice League), positioned to serve as a romantic foil to male protagonists (Jean Grey, X-Men; Elektra, Daredevil; Sue Storm, Fantastic Four) or cast as a hyper-sexualized villainess (Mystique, X-Men; Poison Ivy, Batman & Robin; Harley Quinn, Suicide Squad). However, among this extensive catalogue of underserved women with superpowers appearing on the silver screen, a narrow few have had the opportunity to star in their own pictures. Since the arrival of the new millennium, a period Jason Dittmer refers to as a “post-9/11 cinematic superhero boom,”[1] up until last year, there have been only four female-led superhero films: Catwoman (2004), Elektra (2005), Wonder Woman (2017) and Incredibles 2 (2018). Released in inadvertent couplets just months apart, these two generations of female superheroes, segmented by a 13-year intermission, stand in significant contrast to each other both in their commercial performance and their sociocultural representations of female heroism.

The first wave in the early 2000s was received with poor critical reception and even more disappointing box-office returns—returns with a stench so pungent that it lingered long enough to have reportedly led Marvel CEO Ike Perlmutter to, in 2014, declare women-fronted superhero films “a very bad idea” and “a disaster” in counsel against the company’s prospective venture into “female movies.”[2] Both Catwoman and Elektra have been derided as exploitative uses of the superheroine figure. The New York Times’ A.O. Scott referred to Catwoman as a “teasing S-and-M ballet,”[3] while an AV Club review of Elektra referred to the red bustier-clad protagonist as the “world’s deadliest hooker.”[4]

Contrastingly, the recent second coming of the female superhero has been met with critical plaudit and record-shattering sales. Wonder Woman has the third highest domestic gross of 2017 at over $400 million[5] and Incredibles 2 delivered a box-office weekend debut of $180 million—the best debut of any animated feature ever.[6] So, what changed in the years between these two moments in superheroine cinema? Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 arrived on the heels of a cultural wave of feminine assertion that has seen women warring against discrimination in a host of male-dominated industries (both 2017 and 2018 have been declared ‘The Year of the Woman’). The success of both these films, while merited by their quality alone, has been buttressed by the work of critics who, in the wake of the film industry’s own Time’s Up initiative,[7] have championed for these titles to be recognized as feminist triumphs. But, the feminist approach achieved by the new edition of superheroine can also be found in the superheroine of old. A comparative close reading of the two film pairs presents an assessment of the (anti)feminist messages in Catwoman and Elektra previously condemned by critics, and a reconsideration of the feminist treatises critics have built around Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2.

Selection Process

This essay excludes from its analysis television series’ and those films that predate or lie outside of the big-budget formula of today’s various studio-led franchises. This limited scope allows for an in-depth examination of the post-2000 critical landscape and is not intended to be an exhaustive study of the genre. The inclusion of the PG-rated animated film, Incredibles 2, which is unlike the other PG-13 rated live-action films, is dictated by a critical consensus that has consistently classified the Pixar franchise as a member of the superhero genre, regardless of its marketability to children and families. Admittedly, its designation as a female-led superhero film is a more contentious qualification. Dr. Nadine Wreyford, research fellow with a UK-based research council on women in contemporary film, found that Incredibles 2 had a three to one ratio of male to female characters with speaking roles,[8] with Mr. Incredible, the first film’s unequivocal star, still playing a significant role in the second. But, Incredibles 2 earns its rank among the small school of female-led superhero films, as Elastigirl is undoubtedly the driving force behind the narrative action of the film. A small handful of films were omitted from this study, counted among them are Kick-Ass (2010) and Fantastic Four (2005), which were both discounted because their female characters function as supporting characters. Others, like the romantic comedy My Super Ex-Girlfriend (2006) starring Uma Thurman or the campy sci-fi comic adaption Tank Girl (1995), lean too heavily into tropes outside of the superhero genre to be considered for the intents and purposes of this female superhero catalog.

Catwoman: Sexual Repression and the Emancipation of the Female Body

Leather is the language of the female superhero. Superman, Batman, and Thor may wear capes, but can they fight crime in cut-out chaps like their female colleagues? It has long been an argument of feminist theorists that the fetishized wardrobe of superheroines is the superfluous effect of what Laura Mulvey cites as the male gaze—a term that refers to the camera’s tendency to frame the female figure as a sexual object for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer.[9] The needless costuming of superheroines in high heeled shoes, bare midriffs and latex, functions not only as an impractical depiction of crime fighting but also as a purveyor of her sexualized image. As described by Richard J. Gray, “the leather jumpsuit…serves as a ‘second skin,’ which from the perspective of the viewer, allows all of the nooks and crannies of the female body to be displayed.”[10] The 2004 film, Catwoman, is among the most relentless cinematic uses of such dominatrix-styled voyeurism. Directed by the mononymous filmmaker Pitof and starring Halle Berry, Catwoman’s ensemble has been counted among the most “unnecessarily revealing movie costumes”[11] in history and described by one critic as “so-in-your-face it’s not sexy”[12]. Berry, dressed in a black bra-top and torn-apart leather pants, plays Patience Phillips, an introverted graphic designer who works for behemoth cosmetic company, Hedare Beauty. One evening, in an unfortunate happenstance, Patience overhears the company executive, Laurel Hedare, played by Sharon Stone, discussing the sinister secret behind the success of Hedare Beauty’s makeup products. After her eavesdropping is discovered, Patience tries to flee the company grounds but is murdered by Hedare’s henchmen. Patience’s fate is reversed, however, when she is reborn as Catwoman, a mystical creature with catlike reflexes and shrewd intuition.

Patience’s metamorphosis into the nimble feline vigilante is saturated with sexually-charged images of Berry licking not just her screen-mates but even herself—in one instance, ordering a glass of milk from a bar and then sensuously lapping the residual cream off her lips.

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone remarked, “so much for feminism,” in an unforgiving 200-word review evaluating the superheroine’s crimefighting “cat suit.”[13] The film is unrelenting in its desire to demonstrate Catwoman’s newfound libertarian sexual prowess, but its hypersexualized modes of representation are not without purpose. Catwoman places sexual politics at the center of both its imagery and its narrative; while one sells sex, the other sells feminism, respectively. The film’s dialogue and narration are littered with the mantras of second wave feminism’s calls for self-actualized female sexuality, of which the pioneering feminist Kathie Sarachild once called, “our only possible weapon of self-defense and self-assertion.”[14]

Catwoman’s ultra-eroticism is matched by dialogue that refers to early tenets of feminist thought, aimed at freeing women from the cage of femininity.[15] In a conversation between Patience and the shaman-figure, Ophelia, who guides her through her transition to ‘catwomanhood,’ the film’s feminist approach is made overwhelmingly transparent as Ophelia explains to Patience her new abilities as a Catwoman:

OPHELIA: Catwomen are not contained

by the rules of society.

You follow your own desires.

This is both a blessing and a curse.

You will often be alone

and misunderstood. But you will experience a freedom

other women will never know.

You are a catwoman.

[…]

PATIENCE: So, I’m not Patience anymore?

OPHELIA: You are Patience.

And you are Catwoman.

Accept it, child.

You’ve spent a lifetime caged.

By accepting who you are,

all of who you are…

…you can be free.

And freedom is power.[16]

Unlike her comic counterparts, who see their image sexualized in service of a male audience, Catwoman’s overt sexuality is political for its inherent ties to her character’s ascent into self-actualization. Whereas Patience has been repressed by societal norms that subjugate her to a life of sexual reticence, Catwoman is unhinged from the social conventions of womanhood. It is Catwoman’s sexuality that leads her to reject the genre’s romantic pull toward patriarchy, embodied in her square-jawed suitor, Detective Tom Lone (played by Benjamin Bratt). Patience begins an affair with Lone while her alter ego evades arrest under his investigation into a series of crimes committed by Catwoman. Ultimately, Patience casts Lone aside in a nonconformist rebuttal to traditional patriarchal standards of behavior. In her concluding monologue, Catwoman boasts, “You’re a good man, Tom. But you live in a world that has no place for someone like me.”[17]

Catwoman’s desire to “live a life untamed and unafraid”[18] takes primacy over a historical pedigree that encourages women to find self-value in marriage. A romantic relationship between Catwoman and Lone is made impossible not by his refusal to accept her as a radically empowered female figure, but by her own distaste for structures of patriarchal restriction (embodied quite literally in one scene when, while detained under arrest, the impatient Patience writhes and contorts her body to fit through the narrow bars of a jail cell to escape capture). As Patience explains to Lone in their final scene together: “In my old life, I longed for someone to see what was special in me. You did, and for that you’ll always be in my heart. But what I really needed was for me to see it. And now I do.”[19] In this farewell to Lone, Catwoman recognizes that her own subordination is tied to a patriarchal system, which she has internalized and normalized through heteronormative acts of validation. With Catwoman, a figure who finds no value in such a system, Patience is emancipated.

Elektra: Hardbodied Maternalism

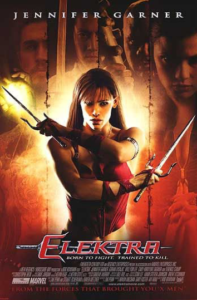

Following the hyper-feminized poise of Berry’s cat-lady, is Jennifer Garner’s role as the green-eyed assassin, Elektra. Released just one year after Catwoman, critics like Maitland McDonagh of TV Guide magazine were quick to liken Elektra to the “pinup appeal”[20] of her cinematic predecessor. Manohla Dargis, in her review for the New York Times, wrote that Elektra “looks like she was drawn by a man with a deep familiarity with the oeuvre of Russ Meyer,”[21] the famed 1960s sexploitation director. Elektra sports the uniform not of a lethal martial arts trained ninja but, as the Washington Post put it, of a woman “auditioning for a spot on the next Victoria’s Secret TV special.”[22] Donning a firm breasted red bustier with silk trousers to match, Elektra’s sultry costuming is inarguably gratuitous, but it does offer a new lens from which to view the female superhero body.

Garner made her debut as Elektra in 2003 as the pugnacious love interest in Daredevil, a thankless role that, to the credit of director Mark Steven Johnson, managed to showcase Garner’s hard-earned musculature. Her toned physique gets its first on-screen introduction during a fight sequence with co-star, Ben Affleck. Affleck, as the blind lawyer Matt Murdock, is conservatively dressed in a suit and tie while Elektra, stands bare-armed, ready for combat in a thinly strapped tank top. With broad shoulders and chiseled arms, Elektra’s physicality commands the screen, overshadowing Murdock’s doughy figure, dubbed by the online news site Salon “almost androgynous” for his soft-bodied appearance.[23] Likewise, Garner’s Amazonian build did not go unnoticed by media. A Telegraph profile of Garner’s role in Daredevil featured the subtitle “…her muscles put Ben Affleck…to shame” with the piece later remarking that Garner’s “biceps [were] rippling under her T-shirt.”[24]

Two years later, when she reprised the role of Elektra for a solo feature, this time armed with a detectably sturdier build, Garner’s brute athleticism was critically disregarded. In a recent essay on the film, Brown University professor, Michael D. Kennedy, went a step further, not just overlooking Garner’s muscly stature but working to undo its existence all together. Kennedy stated, “Jennifer Garner’s version…rejected the more transgressive muscular action heroes (Ellen Ripley, Sarah Connor) in favor of an empowerment featuring ‘slim, white, heterosexual feminine beauty’ for the consumption of the male gaze.”[25] The hardbodied women to which Kennedy refers are a legion of female characters who lead their own action films (i.e., Terminator, Aliens, Blue Steel, Point of No Return), all popularized in the 1980s. As explained in Jeffrey A. Brown’s writings on the gendered fetishization of action heroes, “the well-toned, muscular female body…is presented in these films as first and foremost a functional body, a weapon…The cinematic gaze of the action film codes the heroine’s body in the same way that it does the muscular male hero’s—as both object and subject.”[26]

The framing of the robust female body as a tool of lethal function is a visual trope exploited throughout Elektra. A chiaroscuro effect is often employed in the cinematography to emphasize the contours of Garner’s hardened biceps and abdomen as distinctly athletic. In a scene that is germane to the film plot and included only to demonstrate Elektra’s sheer muscular force, a training montage shows Elektra executing an arduous workout that includes one-armed pull ups and a calculated jump rope routine. The lighting in this sequence mimics a similar backlit glow James Cameron’s Aliens (1986) used to frame central action figures like Ripley. The effect is a sharp white glow that reflects on the angular silhouette and outlines the hardbodied figure.

In addition, the artwork of the film’s DVD release advertises Elektra as “Born to fight. Trained to kill,” with the still image of Garner cross-armed with a pair of her single-pronged metal blades in each hand.[27] Once again, her muscular body is fashioned prominently and accentuated by the effect of the incandescent glow from behind, in a glorification of her brawny bicep similar to that of the Terminator 2’s gun-wielding Sarah Connor.

Elektra’s hardened images of feminine heroism are far from what Kennedy has described as a “rejection” of the celebrated female “badassery” established in Regan-era action films, though there is room for critique of its representational approach. Some theorists have noted the belittling effect such a masculinized imagery can have on the female figure functioning under binary gender codes. Brown writes,

the image of heroines wielding guns and muscles can…render these women as symbolically male…[The] binary structure situates men as active, women as passive…Thus, within this strict binary code the action heroine, who fights and kills on par with men, confuses the boundaries and is seen by some critics as a gender transvestite…[the] notion of the hardbody heroine as a male impersonator.[28]

The legitimacy of these roles is interrogated for their inability or unwillingness to present acts of female heroism as anything other than simply imitations of masculinity. A concern for which Elektra offers a response.

Claims of the chiseled Elektra as a masquerade of performative masculinity are silenced by her character’s push toward maternalism. When we are first introduced to Elektra, her demeanor is that of a woman inured to violence and impervious to affection. Labeled at the beginning of the film as a “non-existent woman,” she is a motherless mercenary who, in the absence of the maternal link, is characteristically unfeminine in profession and behavior. That is, until she meets Abby, the young ingenue who fulfills her call to maternalism. After Elektra discovers that her latest assignment is to execute Abby and her father, with whom she has just recently become acquainted, Elektra is compelled into a role of matriarchal authority, forced to protect Abby and her father, Mark, from the dangerous horde of ninjas who seek to apprehend them. Thus, she becomes a mother-figure and adopts a role as protector. In one scene, Elektra looks to Abby, seated in the backseat of a pick-up truck blowing bubbles out of chewing gum, and murmurs to herself in disapproval, “I’m a soccer-mom.”[29]

During an earlier scene, Elektra yells at Abby from across the dinner table for using profanity, in an exchange clearly meant to satirize the clichés of traditional American family life. Though it is worth mentioning that Abby’s father, Mark, is also seated at the table during this spat and he too barks at Abby for her foul language, it is Elektra’s stern and commanding voice that emerges first as the dominating figure of authority. Furthermore, there is a brewing romantic subplot with Mark that leaves room for a reading that might suggest the relationship reinforces patriarchal norms, but such an interpretation overlooks the narrative’s countless demonstrations of matriarchal dominance. When under peril, Elektra and Abby function as protectors to each other and Mark, who possesses none of their physical ability or combative skill. Unable to protect himself, Mark is rendered the ‘helpless damsel.’ The film’s depiction of superheroism is subtly transgressive in its representation of a female hardbody that can simultaneously function as the maternal figure central to the narrative. As Brown says, Elektra “straddles both sides of the psychoanalytic gender divide. She is both subject and object, looker and looked at, ass-kicker and sex-object.”[30]

The Return of the Superheroine: Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2

It would be over a decade before Hollywood would attempt to place the female superhero at the front of a blockbuster-budgeted action film again. With Catwoman and Elektra proving to be huge financial letdowns for studios, it was feared that the ill-received pictures had irrevocably soured public appetite for superheroines on the big screen. One Elle magazine critic wrote that the failed attempts unjustly fostered a “conventional Hollywood wisdom…that female superheroes aren’t bankable,”[31] while a 2014 BBC article cleverly dubbed it “Catwoman’s curse.”[32] But by 2015, Warner Brothers, healed from the wounds of its lost investment in Catwoman, decided to advance on a standalone film for the beloved comic book character, Wonder Woman. They placed a female director at the helm (Patty Jenkins), furnished her with a $180 million budget, and anxiously waited to see where the chips would land.

At about the same time, Pixar, who had garnered huge commercial success developing sequels to old properties (Finding Dory, Cars series, Toy Story series, Monster’s University) announced a follow-up to its 2004 animated mega-hit, The Incredibles. The sequel, Incredibles 2, would focus on Elastigirl, the superheroine wife to the first film’s male lead, Mr. Incredible. Both Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 nearly burst their profit margins at the seams, ushering in a welcomed farewell to the bygone superheroines who had come to represent all the risk and none of the reward of a female superhero film. These succeeding superwomen were not simply an improvement on their poor-quality progenitors, they were considered by many to be a feminist rebuttal to them. Wonder Woman has been referred to as a “masterpiece of subversive feminism”[33] (The Guardian), “a beautiful reminder of what feminism has to offer”[34] (Washington Post), and “the feminist we’ve been waiting for”[35] (The Daily Beast). Likewise, Incredibles 2 communicates a “triumphantly feminist message”[36] (Metro) as it pushes “for female empowerment, gender equality”[37] (Variety), “delving into the fragility of the male ego in a world where women are asserting themselves”[38] (Time). The resounding critical perception asserts that Wonder Woman and Elastigirl managed to succeed where Catwoman and Elektra had not. The overwhelmingly positive reaction to the new-age superheroine is due, in part, to a contemporary critical lens that has been filtered through the Trump-era sociopolitical landscape. While both Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 are arguably better films than Catwoman and Elektra—superior in performance, special effects, screenplay and overall production value—the newfound critical appreciation for these representations of superheroism as transgressively feminist draws attention to its glaring absence from the critical discourse fourteen years ago.

A sharp turn in the sociopolitical climate over recent years has been influential in reframing the millennial superheroine as a feminist icon. The election of Donald Trump in 2016 inspired a national women’s movement, the results of which are still ongoing, but so far has seen more women take office at the state and federal level than in any other period.[39] Historic worldwide protests voiced an outpouring of fury over Trumpian rhetoric about women, in a massive show of resistance and female assertion. This movement of twenty-first century feminism was compounded by an onslaught of sexual misconduct allegations that made headlines with the hashtag “MeToo,” publicly accusing powerful men across a range of industries. This proved to be a watershed moment as, one-by-one, media giants like Harvey Weinstein and Pixar’s own John Lasseter, were deposed by the emboldened victims of their sexual misconduct. Not invulnerable from these sociopolitical circumstances are the film critics tasked with evaluating Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 amidst this cultural zeitgeist. Writing for the Washington Post, Henry Godinez called Wonder Woman “the perfect hero for the Trump Era” in a deeply personal review that labeled the film “eerily apropos at this moment in our nation’s history.”[40] A Los Angeles Times interview with the Incredibles 2 cast and director anticipated the sequel “might resonate in the era of #MeToo.”[41] The pre-Trump climate that birthed Catwoman and Elektra in the early 2000s, was less inclined to laud cinematic superheroism for its feminist statements. The present-day critical discourse failed to fully contend with the representational misgivings of contemporary iterations. There are three points of contention for critics to consider in their feminist analyses of Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2.

First Consideration: How Setting Frames Political Argument

The setting of Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 becomes essential in an analysis of their feminist approaches. Place and time imbue narrative with the political and cultural issues of the period in which the story is set. For Catwoman and Elektra, contemporary society offered a sufficient canvas for the films to affix their feminist messages. Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 plant their feminist roots firmly in eras of the past. This, as culture critic Hoai-Tran Bui argues, permits the films to grapple with outmoded gender politics that deal with antiquated social concepts well-addressed in first and second wave feminism and bypass the more tendentious elements of modern-day feminism (i.e., intersectionality and the changing discourse surrounding ‘victimhood’).[42]

When superheroine, Diana Prince departs the lush pastures of her native Themyscira to fight alongside mankind during World War I, her journey brings her to confront gender-baiting lines of dialogue like, “What the hell were you thinking bringing a woman into the chamber counsel?”[43]—after she invites herself in to observe a British cabinet meeting. Because Themyscira is an island of Amazons, inhabited only by females, Diana is oblivious to the political disenfranchisement of which early twentieth century women were accustomed. In another scene, after a character explains to her the job of a secretary, Diana bluntly says, “in my country we call that slavery.”[44] The scene is intended in good humor, but still delivers a message disapproving of the scarce economic opportunities afforded to women in the workplace at the time. Diana is confounded by mankind’s sexism, a quality the film uses to articulate its feminist opinions.

In Incredibles 2, the adventures of Elastigirl take place in a sleek cityscape that vaguely situates the film somewhere inside the aesthetic of the Eisenhower-era but imagined lightyears ahead, using the visual motifs of The Jetsons as a prototype. The setting is manifest through characters costumed in 1950s wardrobes and a highly stylized mid-century modernist architecture that satisfies the film’s nostalgia for a period well-suited to the narrative’s gender politics. Unlike The Incredibles, which characterized Bob Parr as breadwinner and Mr. Incredible as patriarchal hero while Helen/Elastigirl tended to household, Incredibles 2 reverses those gender roles. After Helen is asked to become the face of a new PR campaign to legalize superheroes, Bob must endure domesticity while Elastigirl gets to be the face of heroism. The effort for superhero legalization is led by a media conglomerate called DevTech that aims to market Elastigirl as the poster-woman for “supers” by broadcasting television spots where she empowers young women with lines like, “Girls, come on… Leave the saving of the world to the men? I don’t think so.”[45] Elastigirl’s message is informed by the feminist subtext of second wave feminists like Betty Friedan who called for women’s increased involvement in the labor force in 1963.[46] The ‘Rosie the Riveter’ rhetoric put forth by Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 is necessitated by their historically-situated backdrops and thus deliberately avoids engagement with a broader conversation about the aims of contemporary feminism. Messages of empowerment that proclaim “girls can save the world, too!” are put front and center, while a more complex discussion of the political implications of what that might require can be conveniently sidestepped.

Second Consideration: The Changing Perspective on the Female Action Hero Costume

The body of the female superhero is perhaps the most scrutinized of any female character in cinema, in large part, because her costume often reveals so much of her figure. Both Catwoman and Elektra were criticized for the gratuitous sexualization of their superheroine bodies through hyper-erotic costuming, a tradition carried on by Wonder Woman and Elastigirl. Wonder Woman wears a gladiator-style miniskirt and corset; the outfit’s minimalism is briefly mocked in the film when Trevor (Diana’s love interest) stops her from publicly removing her coat. As she moves to reveal her battle uniform, Trevor shouts, “You’re not wearing any clothes!” and quickly shields her from public gaze.[47]

The humorous interaction relies on the film’s self-awareness, commenting on the controversy that has long surrounded Wonder Woman’s apparel, or lack thereof. In 2016, after two months of serving as UN ambassador, Wonder Woman quickly had the title revoked after an onslaught of public complaints and petitions declared that she was more of a sex symbol than a feminist icon. Lynda Carter (the actress who formerly played Wonder Woman on the 1970s television series) came to the defense of her character’s suggestive attire by contending, “It’s the ultimate sexist thing to say that’s all you can see, when you think about Wonder Woman, all you can think about is a sex object.”[48] Historically, comic book publisher Max Gaines wanted her character to be seen in as little clothing as possible. As Jill Lepore details in her extensive book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, “to sell magazines, Gaines wanted his superwoman to be as naked as he could get away with,” instructing illustrators to draw her in outfits described as “scantily clad.”[49]

Now under Patty Jenkins, Wonder Woman’s sartorial stylings have been cast under a new light by film and culture critics more willing to find threads of female empowerment in outfits that showcase the female form. One critic at Bustle, an online women’s magazine, gave praise to Wonder Woman for reclaiming “the iconic costume to make it a symbol of strength.”[50] The critical embrace of superheroine costuming that is no more conservative than previous styles—once lambasted for their poor taste—evidences the effect of Trump-era gender politics on public perception.

Equally risqué is the wardrobe of Elastigirl—a custom-made latex bodysuit that is finely tailored to her unrealistically drawn waist-to-hip ratio. Her exaggerated physique has become so infamous that it became the subject of viral online memes and tweets that took notice of Elastigirl’s curvaceous figure, labeling the superheroine “thicc” (a term that describes a sexually-charged full-figured body).

When New Yorker film critic Anthony Lane, made mention of the arousing posture of Elastigirl in Incredibles 2, he triggered a series of social media responses and editorial essays that scorned him for sexualizing the character. Slate magazine said of the review, “Lane objectifies characters meant to embody women’s strength.”[51] The reaction in defense of Elastigirl’s figure marks a changing tide since the last time a superheroine was shown fighting crime in latex and heels (recall Manohla Dargis’ aforementioned critique of Elektra’s costume).[52]

Third Consideration: Post-Feminist Mixed-Gender Coalitions and the Erasure of Individual Feminist Triumph

In a female-led superhero film, there lies the expectation that the heroine will save the day. Armed with superhuman strength and whip-smart instincts, she will arise victorious, having prevailed on her own—or more specifically, without the help of a man. Like the cinematic male heroes who predate her, the superheroine is shown to be capable of fighting her own battles. In Catwoman, the superheroine faces off with villain, Laurel Hedare, in a hand-to-hand fight that employs her acrobatic skill and unshakable endurance. In Elektra, the superheroine spars against five supervillains, aided on occasion by her young female protégé, Abby. In Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 the same is true. Both female superheroes display immense physical strength in one-on-one battles against their evil rivals, however unlike in Catwoman and Elektra, throughout their films, Wonder Woman and Elastigirl are cast in an ensemble supported by the help of men. Wonder Woman teams up with a crew of hired soldiers assembled by her male co-star, Trevor. Wonder Woman is the formidable leader of the group and consistently outshines her mortal teammates with her superhuman acts of valor, but the film’s desire to form a coalition among its male and female characters in the fight against evil is an approach specific to its generation. Elastigirl is also paired with a team of superheroes to help her foil her archrival, Evelyn Deavor’s scheme to permanently criminalize “supers.” A league of six minor characters join Elastigirl in her crime-fighting quest, each of whom possess their own unique superhero trait. It is only with the help of this ragtag team of superheroes and her family, that Elastigirl can thwart Evelyn’s diabolical plan. Both Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 support a message of gender parity, in which feminist triumph is upheld by mixed-gender partnership, but these moments of coalition also work to subvert singular acts of feminist achievement. This new age of superheroine, who forges alliances with her male accomplices, is a contemporary superheroine trope that has been shaped by postfeminist values.

In popular scholarship postfeminism has come to be understood as a reactionary cultural movement that “suggest[s] that equality is achieved, in order to install a whole repertoire of meanings that [feminism] is no longer needed.”[53] As Angela McRobbie explains, “…new gender norms [have emerged] (e.g. Sex and the City, Ally McBeal) in which female freedom and ambition appear to be taken for granted, unreliant on any past struggle… and certainly not requiring any new fresh political understanding.”[54] In her writings on postfeminism and media culture, Mary Douglas Vavrus identifies the “feminist fallacy” of postfeminism: “Texts and trends promoted as feminist, or even pro-woman, do not always hold up as such in meaningful ways. If anything, an absence of strong feminism is more evident in mainstream media.”[55] Vavrus describes postfeminism as distinctly anti-feminist for its apolitical approach, wherein there is the opinion that gender should not matter. Here, the “absence of strong feminism” as presented in the post-feminist approaches of Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2, presumes the achievement of gender parity and in doing so rolls back the representational objective of the feminist superheroine—an objective previously centered on a feminized image of lone heroism.

Conclusion

Both Catwoman and Elektra hold a 10% score on review aggregator site, Rotten Tomatoes, and are regarded as two of the worst superhero films ever made.[56] Nonetheless, these two oft-maligned works exist in the female superhero film pantheon though their contribution to the genre, when not being overlooked, is often disparaged. Critical reception to these two early aught-age films has extended beyond a discussion of quality and ventured into commentary on their anti-feminist representations of female heroism. One opinion piece for Wired.com protested “The main plot begins with Halle Berry’s character being killed over…face cream. Is it any wonder Catwoman wasn’t a success?”[57] After over a decade, the return of the female superhero has been embraced by many critics for finally getting it right. Most curious in all of this is the critical embrace of the feminist approaches in Wonder Woman and Incredibles 2 despite room for criticism, old and new, of the ways this new era of superhero films present their female leads. As outlined in this essay, a change in critical attitudes perhaps brought on by the contentious sociopolitical landscape is relevant to understanding this shift. This essay endeavors not to compare the quality of these four films, but to consider how the reception of their overlapping feminist messages could be so drastically different.